The Dutch Archaeological Fieldwork

Project at Geraki

![]()

The Dutch Archaeological Fieldwork

Project at Geraki

![]()

As early as the second century AD the beautiful village of Geraki

was very popular among travellers. At that time the famous Greek

traveller and writer Pausanias visited Geronthrae, as Geraki was

called in antiquity, and witnessed its fine architecture.

Although the buildings Pausanias described are now gone, Geraki

has not lost its appeal, for the summer of 1998 will be the fo

the members of the Dutch archaeological fieldwork project will be

working there. Most of Geraki's inhabitants probably have already

become acquainted with our team during the past three years.

Nevertheless, we would like to seize this opportunity to

officially introduce ourselves and explain what kind of research

we are doing at Geraki and for what reason.

The aim of classical archaeology is to reconstruct society in

antiquity in all its aspects. The principal method for doing this

is excavation. The finds resulting from excavation tell us a lot

about what happened at a site, for what purpose it Was used, in

what period it was occupied, etc. And we are not only interested

in monumental architecture or gold treasures; objects like

rooftiles or plain pottery also provide us with a lot of

information. The director of our project is Professor Johan

Crouwel, who makes all the arrangements for our work. The three

other professional archaeologists, who return to Geraki every

year, are Mieke Prent, Stewart MacVeagh Thorne and Els Hom. They

all come from the University of Amsterdam, except for Stewart,

who lives partly in Athens and partly in Boston in the United

States. Each year a group of students is selected to come along.

Some of them have worked in Geraki for two seasons already and

will return this summer. Other students came along once and then

made way for new students to work with us in the following

season.

Besides archaeologists, our team consists of specialists from

other universities and disciplines. For example, during the past

two seasons we were joined by an archaeologist from Nijmegen, who

studied the spolia in the Byzantine churches of Geraki. Last year

Els' sister Ans, a professional teacher of art, joined us to draw

the finds for publication. She will he working with us again this

summer.

Before giving a more detailed account of our work at Geraki,

something should be said about the motives for starting the

project. There are a number of sources which suggested that

Geraki was occupied in antiquity. The first source is the

acropolis itself, because it dominates the large plain around the

village. In antiquity people used to live on hills, mainly

because settlements on hills were easier to defend than those in

plains. The wall around the top of the acropol is supports this

suggestion.

The Byzantine churches in and around Geraki also provide a lot of

information about classical antiquity. These churches were built

partly of ancient architectural blocks. Some of these fragments

originally belonged to ancient monumental buildings. perhaps even

to an ancient Greek temple.

A striking example of this reuse of ancient building material is

the south wall of the Agios Ioannis Chrysostanos. The three

marble blocks forming the doorway contain an important Roman

inscription from the fourth century AD. The same inscription - a

Prize Edict of emperor Diocletian - was found all over the Roman

Empire in the more important towns. The fact that this

inscription has been discovered in Geraki indicates that it must

have been a place of importance during the later Roman period. In

addition to material sources, there are also written ones Wvhich

refer to occupation in Geraki in antiquity. Pausanias was the

first to describe ancient Geronthrae in chapter 22 of book 111 of

his book. According to Pausanias there were two temples in

Geronthrae. One belonged to Ares, the god of war; it has been

located at a spot called "Metropolis", a few hundred

metres south-west of the village. The second temple Pausanias

described belonged to Apollo and was situated on the acropolis.

He also mentioned the ivory head of a statue of the god.

By the beginning of this century the British archaeologist Alan

Wace took a special interest in Pausanias' testimony of Geraki

and started digging a few test-trenches on the acropolis in 1905.

Wace found many interesting objects, but the one thing he wanted

to discover most of all, the sanctuary of Apollo, was not found

and he left Geraki after a few weeks.

The finds recorded by Wace date from the Early Bronze Age

(3000-2000 BC) to the Middle Ages. Among these were graves,

fragments of sculptures, inscriptions, but also the capital of a

column, which probably belonged to a temple. A curious detail is

that nowadays it is impossible to locate the exact spots where he

excavated. He indicated his trenches quite precisely on a map in

his diary, but used trees as fixed points, logicaly assuming

trees would not disappear in a short period of time.

Unfortunately these trees have been cut down some time between

1905 and now, which leaves the map impossible to understand.

These material and written sources led to the start of the Dutch

project in 1995. With its work it aims to reveil more of Geraki's

secrets. The results will be of interest not only for our

knowledge of Geraki's history, but for that of entire Laconia as

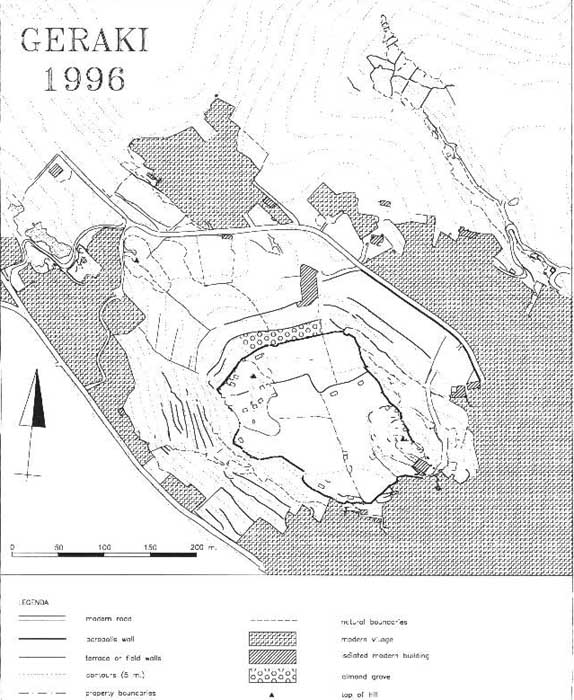

well. During the first two campaigns of the Geraki project, in

1995 and 1996, the fields on and around the acropolis have been

surveyed. This was done by intensive exploration of the surface

of the fields. It was surprising how many ancient objects were

found. Every day a large number of finds were brought to the

apothiki, which was based in the house of the Pandazi family in

1995 and in Giorgos Fratis' house the two following seasons, to

be washed, inventoried and examined. Finally, they were stored in

the Archaeological Museum of Sparta. The results of the two

surveys confirmed the theory that Geraki had been occupied during

a long period in antiquity; from the Early Bronze Age to the

Middle Ages. Among the objects found were some marble fragments

of sculptures, a small Roman statue, made of bronze, miniature

pots, which the Greeks used to offer to the gods and large

numbers of potsherds and rooftiles. Many artefacts, made of stone

and obsidian (a vulcanic glass from the Cycladic island of Melos)

dating from the Early and Middle Bronze Age, were found in the

entire surveyed area as well.

On the basis of the results of the two survey seasons, a number

of fields was selected for test excavation. The excavation of the

selected fields took place during the summer of 1997 and lasted

five weeks. The work was carried out with the indispensable help

of workmen from Geraki and Aphyssou. The test excavation

concentrated on a number of spots both on top of the acropolis

and on its slopes, with the aim to find out what part would be

most interesting to excavate on a larger scale in the future. The

results were very promising, especially on the top of the

acropolis. As said before the acropolis was occupied as early as

the third millenium BC. Around 2500 BC the entire acropolis seems

to have been destroyed by fire and abandoned. This is visible by

a layer of burned earth, which was recorded in all the excavated

trenches on the top of the acropolis. Especially interesting was

a building in the north-east part of the acropolis, dating from

this period. It probably had an administrative function, because

of the finding of a number of seal impressions, and burnt down

completely during the fire.

After the destruction the acropolis was inhabited again. Objects

of nearly all intermediary periods were found. Among these were a

number of tile-graves, probably dating from the Hellenistic

period and spread over the entire acropolis. The most spectacular

finds were the coins, which all of us and the workmen will

remember. The 54 coins were buried in a small bowl and were made

of bronze and.silver, showing the images of Alexander the Great

and some of his successors. Some coins also carry the image of

the goddess Athena and were minted in Athens. The coins date from

the early Hellenistic period, probably from the third century BC.

The finds resulting from the excavation were stored in the museum

in Sparta as well. This summer we will be in Geraki again. This

time, however, we will not be working on the acropolis, but in

the apothiki only. There, the finds from the past three campaigns

will be studied in greater detail and preparations for

publication will be made. The past three campaigns have been very

successful in all respects. The information gathered so far is of

great value for our knowledge of Geraki and Laconia as a whole.

Hopefully, excavation can be continued in the future. The project

has been successful in other ways as well. It has been a pleasure

to work in Geraki for all the members of the project and we are

all looking forward to going there again in June. The weather is

beautiful, the environment is breath-taking and the population is

friendly, hospitable and helpful. What more could a Dutch

archaeologist possibly wish for?

Leontien Schram

Summer 1998